Trusted Partners: Addressing Foreign Disclosure and Technology Release Barriers Between Australia and the US

- Global Voices Fellow

- Apr 25, 2025

- 14 min read

Mikaela Farrugia, Department of Defence

Executive Summary

Within the United States (US) Department of Defense (US DoD), inefficient technology release practices inhibit the ability for trusted partners like Australia to acquire US-origin defence goods and technologies at speed. In particular, the Technology Security Foreign Disclosure (TSFD) process requires multiple separate committees to approve each release of US capabilities to Australia, delaying acquisitions by several years. These issues are exacerbated by protectionist cultures within the US DoD, particularly in Foreign Military Sales (FMS) and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) acquisitions. US legislation passed through the Fiscal Year 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (FY24 NDAA) investigates these issues and aims to provide Australia some administrative relief for FMS and DCS. To date, however, these reforms have not been implemented.

This policy proposal argues that Australia, as a trusted partner and long-standing ally of the US, should be exempt from TSFD processes entirely. It argues that the Australian Government should advocate for a national exemption for Australia in the FY26 NDAA, providing permanent relief from the TSFD process. This would allow Australia and the US to co-design and co-develop interoperable capabilities at speed. A national exemption for Australia allows both Australia and the US to meet legislated commitments under the FY24 NDAA, as well as strategic commitments to both AUKUS and deterrence in the Indo-Pacific.

Problem Identification

United States’ (US) foreign disclosure policies and practices significantly delay the release of US-origin defence goods, technologies and services to the Australian Department of Defence (Defence), the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and Australian defence industry. Prior to the transfer of US-origin capabilities to Australia, the US Department of Defense (US DoD) and Department of State (DoS) perform the Technology Security Foreign Disclosure (TSFD) process known as the TSFD pipes. These pipes comprise of up to 12 committees that determine if providing US technology to foreign persons would be to the detriment of US national security and technological advantage (Defense Innovation Board, 2024). These committees can take up to 18 months each, delaying Australia’s ability to receive US-origin capabilities by several years (National Defense Industrial Association, 2019). The TSFD pipes particularly impact Australian acquisitions through the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) programs which are a primary means through which the ADF procures military capabilities from the US.

In the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS), Australia committed to increase ADF interoperability and interchangeability with the US by enabling access to US systems and capabilities, including through information sharing (Department of Defence, 2024c). The Australian Government further committed to progress reforms to US procurement policy and information sharing in order to deliver a more integrated Australia-US industrial base (Department of Defence, 2024c). Australia will not be able to meet these commitments if inefficient procurement practices pull time and resources from Australian Defence and defence industry. Delayed technology transfer hinders the ability for both allies to develop interoperable capabilities at the speed required to achieve collective deterrence and meet the challenging strategic circumstances of the Indo-Pacific. An inability to effectively collaborate and cooperate with the US will significantly inhibit the speed and scale to which Australia can create and maintain defence capabilities and will limit the collaboration potential under AUKUS. This puts Australian war fighters at risk and delays the creation and operationalisation of key defence technologies.

Context

The Strategic Landscape

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) states that Australia must enhance its alliance with the US, including through AUKUS, in order to deter through denial threats to the rules-based international order in the Indo-Pacific (Department of Defence, 2023). The 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) calls for increased defence cooperation with the US to acquire technologies needed to enhance Australia’s deterrence abilities (Department of Defence, 2024c). The NDS and Defence Industry Development Strategy recommend that Australia drive interoperability with the US by breaking down the barriers to technology transfer (Department of Defence, 2024c; Department of Defence, 2024a). Addressing these barriers will be critical to increasing interoperability between Australia and the US (Department of Defence, 2024c; Department of Defence, 2024a).

The US has also made similar strategic commitments. The US National Defense Strategy (US NDS) commits to increasing collaboration with allies and partners by reducing institutional barriers, including those inhibiting interoperability and exports (Department of Defense, 2022). In July 2024 a Congressionally mandated Commission into the US NDS published a report criticising the US DoD for its outdated procurement systems and cultures of risk avoidance hampering collaboration with allies. It recommends the US DoD create a presumption of sharing to allies via military sales (Harman et al., 2024). Improving technology release with allies like Australia will be critical to realising US ambitions in AUKUS held by Congress.

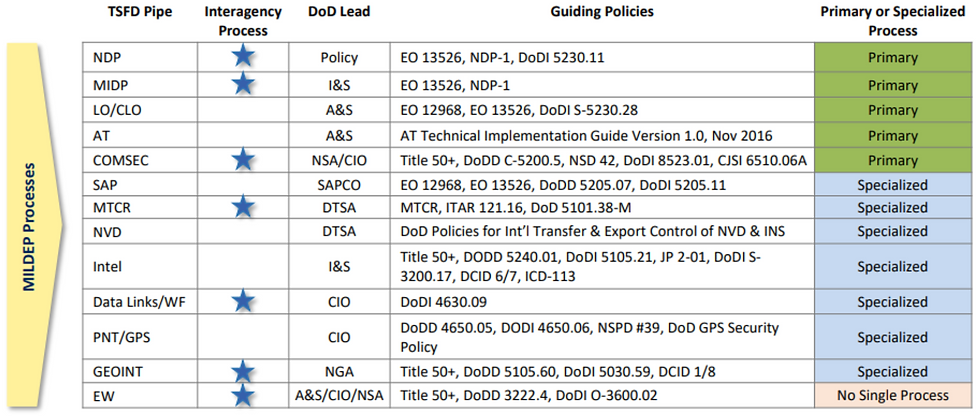

Technology Security Foreign Disclosure Pipes

The TSFD process is one of the greatest inhibitors to streamlined technological cooperation between Australia and the US (Defense Innovation Board, 2024). For Australia to receive US-origin goods or technologies, approval may be required from approximately 12 separate committees or “pipes”. These pipes provide military, intelligence and strategic approval for transfers but also assess if certain partners can access key US technologies like Geospatial Positioning Systems, Night Vision technologies and combat radio frequencies (National Defense Industrial Association, 2019). These pipes determine that transfers to foreign partners are in the US national security interest and will not jeopardise US technological advantage. TSFD acutely impacts FMS and DCS and can delay approvals by several years (National Defense Industrial Association, 2019).

Underlying Policy of TSFD

There is no underlying legislation for the TSFD process. The TSFD pipes are governed by US DoD and DoS policy and various Executive Orders and are dependent on interpretations by TSFD committees (National Defense Industrial Association, 2019). The National Security Decision Memorandum 119 (NDSM 119) is the overarching policy governing TSFD and assigns the Secretaries of State and Defense with establishing and managing interagency procedures regarding technology release arrangements (National Security Council, 1971). US National Disclosure Policy-1 (NDP-1) implements NDSM 119 by establishing policies and procedures for the TSFD pipes (Center for Development of Security Excellence, 2018; Department of Defense, 2017).

Issues with the TSFD Process

US foreign disclosure policy is outdated.

The NDSM 119 remains the primary policy for US DoD disclosure practices, despite being written in 1971. This means that the protectionist policies for working with foreign partners from the height of the Cold War endures as current practice (Monaghan and Cheverton, 2023). Outdated policies based on protectionism reinforces reluctance within the US DoD to share capabilities with partners like Australia.

US foreign disclosure policies are classified, making them inaccessible.

Key policies like the NDP-1 are classified and only accessible by members of the National Disclosure Policy Committee (a primary pipe from FMS and DCS) and particular US DoD employees (Radlin, 2022). Whilst understandable that national security documents should be protected, a lack of transparency surrounding TSFD policies creates confusion and uncertainty in the process. This is exacerbated by the lack of publicly available information about TSFD pipes still operational. Subsequently, partners like Australia possess a limited understanding of core TSFD decision-making and have limited means of growing knowledge in the TSFD process.

Partners must “design for exportability” to ensure navigation of the TSFD process.

Defence industry mitigates TSFD issues by designing to a lower capability level for export to avoid rejection through the TSFD process (Naval Postgraduate School, 2023). As most US acquisition programs do not fund “design for exportability”, industry allocates funds to design circumventions around TSFD instead of investing in capability improvements (National Defense Industrial Association, 2019). Australia, as the purchaser, must then bear these additional costs in their acquisition of US capabilities.

Current Work to Reform Technology Release and Information Sharing

On 22 December 2023, US President Biden signed into law the Fiscal Year 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (FY24 NDAA). The NDAA authorises the annual budget and expenditure for Defence policies and legislation. Within this legislation included several provisions reforming the TSFD process, FMS and DCS.

Section 918 of the FY24 NDAA requires the Secretary of Defense to review the TSFD process to streamline policy and procedures, and increase transparency among stakeholders (FY24 NDAA (U.S), 2023, sec. 918). Section 1341 and 1342 of the FY24 NDAA provides Australia and the UK with priority FMS and DCS processing, including a list of technologies pre-cleared for transfer (FY24 NDAA (U.S), 2023, sec. 1341, sec. 1342). The US DoD, DoS and Congress have not yet actioned or communicated to partners their progress on implementing these new provisions. If the US government is to practically meet these legislated objectives, the TSFD process requires significant reform.

Section 1343 of the FY24 NDAA provides Australia and the UK with a national exemption from US export control licensing requirements. This exemption was conditional on Australia and the UK being certified as having comparable export controls to the US and providing the US with a reciprocal national exemption from their export control licensing requirements (FY24 NDAA (U.S), 2023, sec. 1343). In March 2024, Australia passed the Defence Trade Controls Amendment Act 2024 (DTC Amendment Act), amending the Defence Trade Controls Act 2012 to provide the US and UK with an exemption from Australian export permit requirements (Explanatory Memorandum, DTC Amendment Act (Cth), 2024). The DTC Amendment Act satisfied the FY24 NDAA requirements and Australia, alongside the United Kingdom (UK), was positively certified by the DoS on the 16 August 2024 (Department of Defence, 2024b; Department of State, 2024).

Achieving certification recognised that Australia has equivalent legislation and protections for defence goods and technologies as the US. Australia, alongside the US and the UK, are also signatories to the United Kingdom – United States of America Agreement which formed the basis of the Five Eyes alliance (US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) (Australian Signals Directorate). Five Eyes is a formal intelligence and communication sharing arrangement to share intelligence created to meet complex security circumstances (Fallon, 2022). These commitments have built on the understanding that Australia and the US are trusted partners with equivalent values, security standards and practices.

Options

For Australia and the US to realise joint ambitions of deterrence in the Indo-Pacific, both the policy and cultural barriers in TSFD processes must be reformed to expedite Australian acquisitions of US capabilities. There are several policy mechanisms that Australia can leverage to ease regulatory burdens.

Option 1 - Australia conducts a TSFD reform advocacy campaign and submits a national exemption for Australia from the TSFD process in all cases into FY26 NDAA.

This approach leverages Australia’s existing relationships within the US DoD, DoS and Congress, providing a legally binding, permanent exemption from TSFD within US legislation. It establishes standardised treatment for Australia across all acquisitions and helps the US fulfil its FMS reform agenda legislated through the FY24 NDAA. A national exemption within the NDAA also gives Defence, the ADF and defence industry the transparency and assurance they need to navigate US acquisitions at speed. The NDAA is signed into law by the President in December of every year. Whilst successful for Australia in the past, there is no guarantee that a national exemption proposed by Australia remains in the final version of the NDAA and stays reflective of its initial policy intent.

Option 2 – Australia conducts a TSFD reform advocacy campaign and Australia submits text into the FY26 NDAA which exempts Australia from undergoing TSFD processes for FMS only.

This approach may be more palatable to the US as it would narrow the eligible pool of exempt parties to be the Australian Department of Defence and ADF. This policy option would also assist in delivering some of the FMS reforms signed into law within the FY24 NDAA. This approach would significantly expedite technology release for Australian Defence, increasing opportunities for collaboration and cooperation with the US. An FMS only exemption, however, would largely exclude the Australian defence industry, who would be required to continue complying with current TSFD processes, upsetting Defence’s key stakeholder. Narrowing the scope of a national exemption to FMS only will not address the costs of technology release delays which are forwarded onto Australian Defence as the buyer of US-origin goods by defence industry. Like option 1, this approach would take a year to realise with no guarantee that the exemption will be passed into law as intended in the final NDAA.

Option 3 – Australia negotiates with the US Administration to publish an Executive Order that changes TSFD enabling text in the NDSM 119 and NDP-1, exempting Australia from these policies.

Providing more clear guidance in key policy documents governing TSFD practices would assist in breaking down protectionist cultures and inconsistent decision-making among TSFD committees. Despite not being legislation, Executive Orders have the same enforceability and cannot be overturned by Congress (Knight, 2020; US Bar Association, 2021). This may ensure that Australia receives some regulatory relief from the TSFD process. Executive Orders, however, may be reversed, repealed and rewritten by subsequent Presidents, meaning that there is no guarantee that an exemption for Australia granted through an Executive Order will not be repealed later (Bureau of Justice Assistance). Uncertainty surrounding the future of any relief included within an Executive Order will decrease Australian Defence, ADF and defence industry trust in the reforms and may incentivise the use of the TSFD pipes regardless of whether they are required.

Policy recommendation

It is recommended that Australia pursue Option 1 and conduct a TSFD reform advocacy campaign culminating in the inclusion of a national exemption for Australia from TSFD processes in the FY26 NDAA. This policy option builds on existing relationships and successes that Australia developed through the passage of Section 1343 of the FY24 NDAA. It legislates relief from US technology release processes for Australia, providing clear, transparent and permanent guidance to TSFD committees regarding Australia’s access to US information and technologies. This is critical to combatting protectionist cultures and discrepancies in technology release practices within the US DoD.

Over 18 months, the Australian Department of Defence should conduct an advocacy campaign in consultation with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Australian Post in Washington DC. This campaign will target the US Department of Defense, specifically Defense Technology Security Administration (DTSA) and the Technology Security Foreign Disclosure Office (TSFDO), and the US Congress. These are the bodies responsible for passing the NDAA and implementing its policies.

The advocacy campaign will aim to achieve three things:

To increase understanding of the impacts that inefficient and inconsistent TSFD processes has on Australian capability acquisitions within the US DoD and Congress and how this impacts Australia’s defence and national security;

To garner support among DTSA, TSFDO and the Congress for Australia receiving an exemption from TSFD processes in FY26 NDAA; and

To collaborate with the US DoD to pass and implement the national exemption through the FY26 NDAA effectively to ensure it meets its policy intent.

Defence will create a communications strategy consulted across the Australian Government to ensure messaging is aligned. This strategy would be used across all levels of Government, including at the Ministerial level and by Defence leadership to advocate within the US Administration for the successful passage of a national exemption through the FY26 NDAA.

Policy Option 1 has no additional costs. Costs relating to implementation will be absorbed by Federal Budget allocations to the Department of Defence.

This policy option would be deemed successful if Defence, the ADF and defence industry can report a decrease in the time and administrative burdens associated with progressing through US technology release processes. Defence should conduct regular reviews and audits to determine the effectiveness of the policy every two years after its passage.

Legislative change to TSFD policies through the FY26 NDAA would significantly reduce the delays that the ADF and defence industry experience in the acquisition of capabilities. A national exemption for Australia would also assist the US in satisfying the reform agenda legislated under the FY24 NDAA, particularly for FMS and DCS. Entirely removing technology release delays for Australia will provide a net reduction in the costs of doing business with the US. It will also streamline defence trade between Australia and the US to effectively enable interoperability required to meet the objectives of AUKUS. This is critical to achieving collective security within the Indo-Pacific.

Risks

Appetite of the US to reform TSFD may be limited within the US DoD.

Current inefficiencies within the TSFD process are both caused and exacerbated by deeply rooted protectionist cultures at the working level within the US DoD. Whilst Australia has significant support and influence with the US Congress, it has little visibility and reach into the US DoD. Australia will need to work closely with its contacts within the US DoD (e specially DTSA) to ensure changes are widely and effectively communicated internally. This will ensure uptake among FDO cohorts.

Australia lacks visibility on TSFD policies that are not accessible or transparent.

Whilst legislating a national exemption for Australia from the TSFD process through the FY26 NDAA will significantly improve policy visibility and transparency, the NPD-1 (the primary policy through which TSFD is governed) is classified and likely inaccessible to Australia. This means that Australia has no means of verifying if our policy intent for any TSFD changes have been included or accurately realised in the NDP-1.

The US DoD may request Australia make legislative changes in order to receive a national exemption from the TSFD process.

The US may request that Australia make legislative or regulatory changes in return for receiving a national exemption. Through legislative changes made under the Defence Trade Controls Amendment Act 2024, Australia has been deemed by the US as having comparable export controls and should not be required to make further adjustments to its export control and technology security frameworks. Firm and consistent communication across all levels of US government should convey Australia’s stance against further regulatory reform. This will be critical to managing expectations of the US.

Annex

Annex A - Technology Security Foreign Disclosure Pipes

Annex B - Description of the TSFD Pipes

The TSFD Pipes consist of (National Defense Industrial Association, 2019):

National Disclosure Policy Committee (NDPC): an interagency committee that determines if capabilities can be supplied to foreign partners who are not already approved to receive that level of classified information.

Military Intelligence Disclosure Policy Committee (MIDP): an interagency process run by the Undersecretary for Defense Intelligence, which determines if Military Intelligence can be released to foreign partners. This committee has likely been consumed into the NDPC.

Low Observable and Counter Low Observable Tri-Services Committee (LO/CLO): a committee comprising of the US Army, Navy and Air Force. Determines if stealth or stealth detection technologies can be released to foreign partners.

Anti-Tamper (AT): assesses the risk of proliferation or reverse engineering of US technologies by adversaries and if this would compromise US capabilities.

Communication Security (COMSEC): an interagency process that determines which allies can view and access communication security capabilities.

Secure Special Access Program (SAP): approves the transfer of capabilities related to SAPs.

Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR): an interagency process that assesses if a capability meets MTCR thresholds in line with US commitments to MTCR export controls.

Night Vision Devices (NVD): determines if partners can access US night vision technology.

Intel: an interagency process that determines if databases incorporated into communications systems can be released to foreign partners.

Data Links/Wave Forms (WF): determines if allies and partners can use the same frequencies that the US communicate through in certain combat stations.

Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT)/Global Positioning System (GPS): reviews certain countries against policy criteria to determine if the US Government is willing to provide partners access to precision GPS technologies.

Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT): an interagency process that determines if US mapping capabilities should be included in a sale or transfer to foreign partners.

Electronic Warfare (EW): sub-process within other TSFD pipes that determines if electronic warfare technologies should be provided to foreign partners.

References

American Bar Association. (2021, January 25). What is an Executive Order?, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/publications/teaching-legal-docs/what-is-an-executive-order-/

Australian Department of Defence. (2023). Defence Strategic Review. Retrieved at https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review

Australian Department of Defence. (2024a). Defence Industry Development Strategy. Retrieved fromhttps://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/defence-industry-development-strategy

Australian Department of Defence. (16 August 2024b), Generational export reforms to boost AUKUS trade and collaboration, Media Release, Department of Defence. https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2024-08-16/generational-export-reforms-boost-aukus-trade-and-collaboration;

Australian Department of Defence. (2024c). National Defence Strategy. Retrieved fromhttps://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defence-strategy-2024-integrated-investment-program

Australian Signals Directorate. (unknown). Intelligence Partnerships. https://www.asd.gov.au/about/history/75th-anniversary/stories/2022-03-16-intelligence-partnerships

Bureau of Justice Assistance (unknown), Executive Orders: Justice Information Sharing, Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Government. https://bja.ojp.gov/program/it/privacy-civil-liberties/authorities/executive-orders#2-0

Center for Development of Security Excellence. (2018). Foreign Disclosure Training for DoD. https://www.cdse.edu/Portals/124/Documents

Defense Acquisition University. (unknown). Technology Security Foreign Disclosure (TSFD). [Image]. Retrieved athttps://www.dau.edu/cop/iam/resources/technology-security-and-foreign-disclosure-tsfd

Defense Innovation Board. (2024). Optimizing Innovation Cooperation with Allies and Partners, Defense Innovation Board. Retrieved at https://innovation.defense.gov/Recommendations/

Department of Defense. (2022). National Defense Strategy, Government of the United States. Retrieved athttps://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3202438/

Department of State. (15 August 2024). AUKUS Defense Trade Integration Determination, Media Release. Retrieved athttps://www.state.gov/aukus-defense-trade-integration-determination/

Fallon, S. (2022). Australia’s Security Relationships, Parliamentary Library Briefing Book: key issues for the 47th Parliament , Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Australia. Retrieved at https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook47p/AustraliaSecurityRelationships

Harman, J., et. al. (2024). Commission on the National Defence Strategy, United States Congress. Retrieved athttps://www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/NDS-commission.html

Joint Chiefs of Staff. (2017). Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Manuel 5230.01, US Department of Defense. Retrieved at https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Library/Manuals/CJCSM

Knight, B. (2020, July 09). What Is an Executive Order, University of New South Wales. https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2020/07/what-is-an-executive-order-

Monaghan, S., Cheverton, D. (2023). What Allies Want: Delivering The U.S. National Defense Strategy’s Ambition On Allies and Partners, The National Security Review. https://warontherocks.com/2023/07/what-allies-want-delivering-the-u-s-national-defense-strategys-ambition-on-allies-and-partners/

Naval Postgraduate School. (2023). Excerpt from the Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Acquisition Research Symposium, Department of Defense Management. Retrieved athttps://dair.nps.edu/handle/123456789/4844

National Defense Industrial Association. (2019). Overview of Technology Security & Foreign Disclosure TSFD Release and Designing for Exportability” [Webinar]. Retrieved at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LxaXPz2-9QA

Radlin, A. (2022). How Should the US Military Share Secrets?, RAND. Retrieved at https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2022/10/how-should-the-us-military-share-secrets.html

US Congress. (2023). H.R.2670 - 118th Congress (2023-2024): National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2670/text.

US National Security Council. (1971). National Security Decision Memorandum 119, Government of the United States. https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nsdm-nixon/nsdm-119.pdf

-------

The views and opinions expressed by Global Voices Fellows do not necessarily reflect those of the organisation or its staff.

.png)