Nation-Building Through Education: Financial Literacy for All Australians

- Global Voices Fellow

- Mar 28, 2025

- 17 min read

Updated: Apr 19, 2025

Nicholas Drew, Menzies Foundation Fellow, Y20 Brazil

Executive Summary

Australia has failed to build strong foundations in the area of financial literacy across the generations. Studies confirm financial literacy amongst 15-year-old Australians has declined, with most young people learning about money and budgeting at home (De Zwaan & West, 2023; Singhal, 2017). The current Australian National Curriculum does not recommend personal finance as a subject area (at best, financial literacy is considered in an interdisciplinary context) and consequently, Australia is failing those from non-affluent households and adding further barriers to disadvantaged young people.

This gap results in increased debt, financial stress, and economic vulnerability, with long-term negative consequences for individuals and the broader economy (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2024). If the low levels of financial literacy in Australia remain unaddressed, the consequences will extend beyond individual hardships. It has the potential to affect overall economic stability by contributing to rising household debt and lower overall economic growth (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2024).

In response, this policy paper recommends financial literacy concepts to be integrated directly into the Australian National Curriculum. Essential concepts such as savings, loans, credit cards, insurance, investments, and superannuation need to be taught not just as mathematical calculations, but as real-life skills. This issue impacts all of society; merely offering after-school or broader community information sessions falls short of a comprehensive response. Improving financial literacy skills in young people secures personal freedoms and decision-making abilities for generations of Australians to come.

Specifically, the recommendation proposes integrating ‘personal finance’ as a mandatory content area within the National Curriculum’s ‘Economics and Business’ compulsory subject for Years 7 to 10. The Department of Education, in collaboration with the Australian Curriculum Assessment Reporting Authority (ACARA), is positioned to create initiatives that provide consistent and comprehensive financial education to all students. The projected cost for this initiative is $15 million over 2 years. Following the establishment period, an annual $2 million will be deployed through ongoing program monitoring, evaluations, and updates. A major risk is curriculum ‘integration challenges.’ By removing current content descriptors from 7-10 in the ‘Economics and Business’ subject, and adding ‘Personal Finance,’ teachers will have to redevelop lesson materials.

Problem Identification

Australians continue to rank poorly in financial literacy, with recent studies showing over a quarter of Australian participants struggle to answer simple questions about interest rates, inflation, and investment risks (Hendry et al, 2021). The 2020 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey of 17,000 people highlighted, compared to the 2016 survey, a significant decline in financial literacy among Australians under the age of eighteen (Collett, 2023; Murray, 2020).

Students are not learning personal finance concepts such as where money comes from, budgeting, investing, and financial planning (ACARA, 2022b). These skills are essential for ensuring individuals can effectively manage their personal and professional lives. The Australian Government has recently allocated $11.2 million in adult financial literacy programs, indicating the presence of a systemic issue and a clear foundational gap in the nationwide approach to financial education.

In summary, because Australia’s National Curriculum does not mandate a dedicated personal finance content area, many young people, especially those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, are granted a limited exposure to sound financial education. Failure to include this content area further promotes pre-existing gender gaps with 34% of Australian women, compared to 16% of Australian men, being determined ‘financially illiterate’ (De Zwaan & West, 2023: Wood, 2023). Going forward, it is essential that Australians are equipped with these foundational skills from an early age; ultimately mitigating the future need for upskilling initiatives which results in long term cost savings for all levels of government and community education initiatives.

Context

Financial literacy, defined as ‘the ability to understand and effectively use various financial skills, including personal financial management, budgeting, and investing,’ is essential for the functioning of modern society (Fernando, 2024). Understanding personal finance topics enables individuals to make informed decisions, manage their assets and liabilities effectively, and contribute to the Australian economy. Despite this critical importance, financial literacy is not adequately taught in the National Australian Curriculum, with a focus predominantly being placed on theoretical knowledge, as opposed to practical skills (De Zwaan & West, 2023). This education gap is particularly detrimental to individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, perpetuating cycles of poverty (and in the alternative, cycles of generational wealth) (Garcia & Weiss, 2017).

The Australian Government’s initiatives to date have prioritised the upskilling of adult financial literacy. With a focus on post tertiary education programs, the Government has allocated $23 million from 2024 to 2026 towards programs that improve financial education across the country (Rishworth, 2024).

This spend includes:

$6.3 million of the initial $23 million will fund a no-interest loan scheme aimed at assisting individuals who need to purchase a vehicle for essential use

$4.7 million will enhance accessibility to financial counselling services (Rishworth, 2024)

$11.2 million allocated for the expansion of the Saver Plus program, which helps participants build essential financial skills (Rishworth, 2024).

In Australian schools, financial concepts are only discussed in mathematics subjects. The general mathematics content descriptors seen in Figure 1 (below) demonstrates the formulaic approach applied. This policy recommendation reiterates the need for practical context when teaching financial concepts to young people.

The current approach adopted by the Australian Curriculum to teaching financial literacy is incorporating these skills within the mathematics subject area (Australian Curriculum, 2024). Financial concepts taught within mathematics adopt a calculative approach where students focus on formulas and calculations without real-life practical skills (ACARA, 2022b). Rights and responsibilities surrounding finance are not being taught, with some of the key lacking skills including understanding the importance of money management, information about financial products and services, keeping financial records, and knowing where to go for assistance.

Across Australia’s states and territories, there are ongoing inconsistencies in implementing these limited financial concepts into a range of subject areas. For example, the National Australian Curriculum provides opportunities for financial literacy education within Mathematics while the NSW Curriculum incorporates these skills within their Studies of Society and Environment (Commerce) subject area (NSW Education Standards Authority, 2020). These curriculum inconsistencies between states lead to varied levels of financial understanding among young Australians.

The low level of financial literacy amongst young people is particularly concerning given the range of financial decisions that young people are increasingly required to make. This includes decisions around investing in education, contribution rates to superannuation accounts, and personal financing. Young Australians are also increasingly embracing, along with Australians more generally, arguably risky financial products such as ‘buy-now, pay-later’ (BNPL) services. BNPL services are currently used by 38% of Australians, with $12 billion worth of purchases being made in the 2020/21 financial period alone (McGhee, 2022). This data, paired with previously highlighted finance literacy rate data, demonstrates a concerning trend and flags glaring vulnerabilities.

Financial literacy is not an ‘optional skill,’ but rather a fundamental skill, essential for all Australians to participate in society. From marriage, to transport, to the weekly grocery shopping trip, all individuals are empowered through financial education. However, the current linear approach to financial literacy in the National Australian Curriculum overlooks the dynamic nature of real-world financial problem-solving. Consequently, many young Australians are unprepared for financial independence, relying instead on their parents/guardians for guidance (De Zwaan & West, 2023).

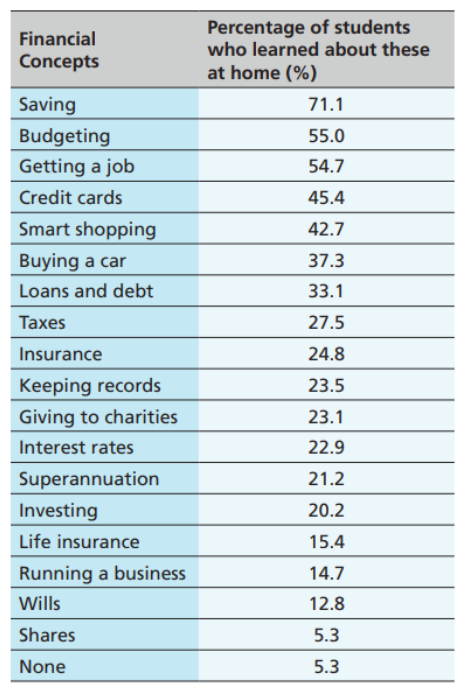

This reliance for financial concepts to be taught in the home can be seen in Figure 2 (below), with over 50% of students learning how to seek employment, budget, and save from their parents/guardians. This reliance is problematic, as a study found in 2020 that 45% of the Australian population is financially illiterate (Preston, 2020). This generates a systematic cycle of economic discrepancies as younger generations are passed down limited or even detrimental financial habits. As Australians age, poor financial literacy leaves individuals vulnerable to financial abuse. A real time example of this is where children abuse their enduring power of attorney in real estate transactions to fraudulently receive property and estate assets before the testator’s passing; coined, ‘inheritance impatience’ (West & Drew, 2023).

The World Economic Forum has identified financial literacy as an essential skill set in the modern age (Nazeri, 2024). The New Zealand Opposition (Labour Party, Christopher Hipkins MP) recently announced their intention to make financial literacy compulsory in secondary schools in 2025 (The Educator Australia, 2024). This policy change would be implemented through existing subjects such as social sciences and mathematics to reduce costs (NZ Labour Party, 2023). Students will learn fundamental skills such as budgeting, how to open bank accounts, managing bills, saving, and investing money (The Educator Australia, 2024).

Case Study

Lessons can be drawn from Denmark, where financial education has been a compulsory part of the National Danish Curriculum since 2015 for students aged 13 to 15. Students learn about budgeting, savings, and comparing financial instruments for their unique circumstances as consumers of an increasingly connected and digitised world (International Network on Financial Education, 2023). This program has contributed to Denmark’s 71% financial literacy rate, one of the highest globally (World Economic Forum, 2024). In contrast, Australia’s financial literacy rate is 45% (Preston, 2020), indicating the need for a more comprehensive and consistent nation-wide approach to financial education. The success of Denmark’s financial literacy program could offer a blueprint for Australia, demonstrating how integrating structured financial education into the National Curriculum can foster a more financially literate population.

Current Legislation

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority Act 2008 (Cth) (the Act) establishes ACARA, as the leading independent statutory authority for curating and mandating Australia’s National Curriculum. Section 6(a) of the Act requires ACARA to create a “Charter,” this is the National Curriculum. Schedule 1 of ACARA’s charter outlines the foundational courses for Years 7-10. ACARA’s primary function, outlined in Section 6, is to develop and administer the national school curriculum, including content and achievement standards for specified subjects. Further, ACARA publishes comparative school performance information and provides resources and guidance to educators. ACARA's operation is governed by Section 4, which ensures that its powers and functions are constitutionally sound, not impinging on the States’ plenary power. Consequently, ACARA must perform its functions in accordance with any directions provided by the Ministerial Council, as specified in Section 7(1).

Options

To build a financially literate community, learning about money management should begin at an early age, empowering all Australians through education of fundamental financial skills. The critical measure of success is increasing Australia’s financial literacy rate and working towards narrowing the gap between children born into high and low socioeconomic households. The below options work towards the defined critical measure, prioritising increased participation for students from non-affluent households. Ultimately, all options work to empower individual financial decision making and reduce economic vulnerability.

Amend the National Curriculum to include 'Personal Finance' as a mandatory content area in the foundation "7-10 Economics and Business" subjects by 2028.

Specifically, Figure 3 (below) highlights the relevant subsection suggested for reform in Schedule 1 of ACARA’s Charter. This option ensures systematic and comprehensive coverage of financial literacy topics. Through integrating financial education seamlessly into existing subjects, the need for additional resources and teacher training is minimised. Additionally, implementing ‘Personal Finance’ into a pre-existing core, compulsory subject prioritises the content. Where the content does not form part of a core subject, the material is susceptible to being removed from the National Curriculum in line with departmental funding cuts or shifts in policy priority.

However, akin to any reform, this option will create more work for individual teachers. Specifically, teachers will have to redraft ‘Economics and Business’ lesson plans and personally upskill in the content. The Australian Curriculum undertakes a six-year cycle of review to ensure that the content continues to meet the needs of students in our ever-evolving world (ACARA, 2023). Consequently, the implementation of personal finance into the Economic and Business subject area, all content material, and teacher readiness needs to be prepared for the next review in 2028. This option has been estimated to cost approximately $15 million initially, with a $2 million maintenance cost.

Offer after-school financial literacy programs open to all students, providing practical financial education through interactive workshops and activities.

This option provides an inclusive and accessible program to students of all ages and backgrounds, allowing for hands-on learning, and real-world application of financial concepts. This program creates an engaging learning environment that encourages critical thinking and problem-solving. Additionally, the inclusive nature of the program promotes equity. Going beyond the classroom environment ensures that all students, including those who may not receive financial education at home, can access this essential knowledge. This option can be tailored to address the unique financial challenges specific to different regions, accounting for the diversity of learning styles and challenges faced by communities across Australia. By adapting the content to regional contexts, the program becomes more meaningful and impactful for students.

However, participation may be limited due to time constraints and extracurricular commitments. Consequently, these programs may not reach all students, leading to inconsistent financial literacy outcomes. Attendance could favour students already interested in or with prior exposure to financial concepts. It is not unreasonable to assume those from non-affluent households may face additional barriers such as limited parental support, lack of transportation, and time constraints due to work or family commitments. In turn, this option may serve to widen the gap and leave those who need this education the most worse off. Another limitation for this program is the extensive funding required to reach all schools and Australian students. These programs may not reach all students, such as those in rural communities. Some schools in remote or low socioeconomic areas, may not have access to community members that can dedicate time to organising an after-school program. The engagement of a third party raises further questions around enablement such as cultural training, travel, and accounting for broader liabilities. Consequently, this option may lead to inconsistencies and inefficiency in the delivery of financial education workshops across Australia.

Widespread funding would be required for resources and materials, including the enabling of third-party educators to travel to these isolated areas when required. The Ecstra Foundation’s principal activity is promoting financial literacy. The Foundation also operates ‘Talk Money,’ one of the largest school targeted financial literacy programs in Australia. The Foundation has worked with over 1,200 schools to deliver this training to 300,000 students. In the 2019 Financial year, the Foundation was founded and received over $75 million dollars in grants and donations to develop the program (ACNC, 2019). In the 2024 Financial Year, the Foundation’s program costs amounted to almost $2.5 million (ACNC, 2024).

Develop a comprehensive online platform with financial literacy resources and interactive modules.

Developing a comprehensive online platform allows for flexible, self-paced learning that can cater to diverse learning styles and schedules. Students can access the platform anytime, making it convenient for those who may struggle to attend in person workshops. Additionally, it can be regularly updated with current financial trends, tools, and resources, ensuring that students learn the most relevant and up to date information. The platform can further serve as a valuable tool for teachers, who can integrate the content into their lessons or supplement it in classroom instruction.

This option builds upon ASIC’s ‘MoneySmart for Teachers’ website, providing materials directly to students (Australian Government & ASIC, 2024). However, this option relies on students having reliable access to technology, which may not be equitable across socioeconomic groups, potentially widening financial literacy gaps. Self-motivation is also crucial for success in online learning, and some students may struggle to stay engaged without guidance or monitoring of learning outcomes. The first five years of MoneySmart cost the taxpayer over $5 million; this was contributed in various amounts by the states and territories (Council of Australian Governments, 2017). To expand the platform from beyond use for teachers in an equitable way would incur significantly more costs. The platform will require ongoing maintenance and updates to ensure information remains accurate and relevant which can be resource intensive. Furthermore, given the plethora of pre-existing online content on financial skills, students may struggle to discern the most reliable or useful resources.

Policy Recommendation

Each of the outlined policy options addresses the need for improved financial literacy education, but they differ in terms of implementation, resource requirements, and potential reach. The integration into the National Curriculum offers the most systematic approach, while standalone courses and afterschool programs provide more flexible options. Integration into schools ensures ACARA-regulated content controls and best-practice information.

Option 1 is recommended to be implemented as the most viable solution to address Australia’s financial literacy gap. Option 1 involves integrating ‘Personal Finance’ as a mandatory content area within the National Curriculum’s ‘Economics and Business’ subject for Years 7 to 10. This initiative would be led by the Department of Education in partnership with ACARA and involve collaboration between the federal and state governments. Educational institutions, teachers, financial literacy and personal finance experts, as well as key community stakeholders would form an essential part in initial and ongoing consultations.

Proposed legislative changes will include amendments to the Act that mandate personal finance education. This policy aims to provide comprehensive financial education to all students, ensuring they are equipped with essential financial skills.

Proposed Amendments to the Act

The proposed amendments to the Act include an addition to Schedule 1 of ACARA’s Charter to explicitly include "and Personal Finance" alongside the core “Economics and Business” content area. In practice, this expansion will cover key areas such as saving, budgeting, and investing to ensure students receive a holistic education in personal finance topics.

Objectives of the Financial Literacy Curriculum

To provide students with the essential knowledge and skills needed to make informed and effective decisions about their personal finance

To prepare all Australians for economic challenges that may be faced in adulthood

To ensure consistency and high educational standards in financial literacy for Australians, for generations to come

Curriculum Implementation

The delivery of financial literacy education will be expanded beyond mathematics and integrated into the 'Economics and Business' curriculum considerations. This approach shifts the focus from purely financial calculations to broader financial concepts and real-world applications. To comprehensively evaluate students' understanding and practical application of financial literacy concepts, diverse assessment methods will be employed. These methods will include written assignments, presentations, oral explanations, and group projects.

Measuring Success

Success will be measured through regular standardised financial literacy assessments, which will evaluate students' proficiency in personal finance concepts and track their academic progress over time. One of the ways this could be achieved is through the addition of a personal finance aptitude test within the National Assessment Program - Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN). NAPLAN assessment results are a central part of ACARA’s analysis of student performance (ACARA, 2023).

The testing of financial literacy, as a core content module in NAPLAN, would provide insight to the development of attitudes towards money in students between Year 7 and Year 9. NAPLAN performance will be analysed to gauge the effectiveness of the curriculum and identify areas for improvement. Further, students' financial behaviours and attitudes toward money management can be assessed through the commission of annual comparative study of “Financial Concepts Learned at Home” vs “Financial Concepts Learned at School” (as in Figure 2 above), to assess the efficacy of financial literacy education in schools.

Additionally, feedback from educators, students, parents, and other stakeholders will be gathered to continuously improve the curriculum and its delivery, ensuring the content continues to meet the needs of all students.

Predicted Costs

It is estimated the implementation of a new financial literacy curriculum component will cost $15 million over 2 years. Costs breakdowns are outlined below:

Item | Estimated Cost | Cost Determinants |

Curriculum development and website update | $2 million | ACARA spent $466,000 in 2023 for curriculum development consultants (ACARA, 2023). ACARA spent $407,000 in website development in 2023 and $13.3 million in employee wages (ACARA, 2023). |

Teachers’ Professional Development Training | $6 million | The Australian Government spent $72.4 million on teacher professional development opportunities from 2023 to 2024 (Department of Education, 2024). |

Resources and Materials | $5 million | In the 2021/22 financial year, the total recurrent government funding for schooling was $78.69 billion (ACARA, 2023). |

Administrative Costs | $2 million | On-going program assessment effectiveness, monitoring, evaluations, and updates could be an annual $2 million (ACARA, 2023). |

Total | $15 million |

Limitations

Curriculum Integration Challenges

To reduce overload to the current curriculum, a content descriptor from the ‘Economics and Business’ subject from Years 7-10 would need to be removed to make room for a personal finance content descriptor. For example, the Year 7 content descriptor ‘characteristics of entrepreneurs and how these influence the success of a business’ (AC9HE7K03) could be removed. This could be a limitation because removing existing content might lead to gaps in student understanding of broader economic principles and entrepreneurial skills. Additionally, this shift might cause resistance from educators and stakeholders. Another limitation is the upskilling of teacher knowledge as not all educators may be financially literate themselves. Teachers will need extra planning days with colleagues to redraft lesson plans, create new success criteria and update unit outlines to accommodate for the new financial literacy content descriptor.

Cultural and Socioeconomic

The curriculum must be designed to be relevant and accessible to students from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Failure to do so might lead to inequities in financial education. Engaging students who come from varied backgrounds and have different levels of prior knowledge and interest in finance can be challenging. To mitigate this risk, the content must incorporate culturally responsive teaching strategies and differentiated instruction that addresses the diverse needs of students. This may include providing content that reflects the financial experiences of various cultural and socioeconomic groups, ensuring that examples and case studies are relatable and relevant.

Sustained Commitment

Ensuring sustained commitment and continuous improvement of the curriculum requires ongoing support, funding, and adaptation to changing financial environments. To mitigate this risk an advisory board composed of educators, financial experts, and other stakeholders, through consultation, can ensure the program’s ongoing effectiveness and relevance in an ever-developing world. Embedding financial literacy within the core compulsory subject of ‘Economics and Business’ ensures that the content remains a priority in education and is less susceptible to funding cuts or shifts in policy. Professional development for teachers on new financial trends and teaching methods can further support the curriculum’s success and adaptability.

Economic Stress

Discussing financial concepts such as debt and budgeting might cause stress for students from families experiencing financial difficulties, potentially affecting their engagement in the subject. Professional development days can support teachers in approaching financial concepts with sensitivity, inclusivity, and focusing lessons on practical skills rather than highlighting financial struggles. Incorporating diverse scenarios that reflect different socioeconomic backgrounds can make the content relatable without targeting student's personal circumstances.

Risks

Federal-State Coordination

Given that education is a matter delegated to individual state responsibility, there is a risk of coordination challenges. Challenges may arise between the Federal Government, which is responsible for developing and funding the National Curriculum, and State Governments, who are responsible for implementing educational policies (Australian Constitution, 1901). Ensuring alignment and cooperation between federal and state authorities will be crucial to the successful integration of personal finance education into high schools. Through a non-partisan drafting and consultation process it is hoped that a nationwide investment is made in this reform. It is essential that this policy reform remains centred on equipping younger generations with essential life skills. Active participation from stakeholders across the board will ensure the ongoing support of this policy irrespective of election cycles or cyclical policy considerations.

Resistance from Education Providers

Schools, whether private or public, may resist the introduction of mandatory personal finance education. This policy reform may be viewed as violating individual school autonomy and a diversion of resources from other priority content areas. Of the allocated $15 million, $6 million should be dedicated to teachers’ professional development to mitigate these concerns. This investment will ensure that schools, along with their educators, are equipped with the skills and resources needed to effectively teach financial literacy.

Philosophical Opposition

Some stakeholders may argue that schools should focus solely on teaching critical thinking ability rather than practical day-to-day skills. Overcoming this philosophical opposition will require demonstrating the real-world impact of financial literacy on individuals and society, highlighting the importance of equipping students with practical skills. Outlining the success of similar curriculums implemented overseas may assist with this and help turn the crank of change in Australian education policy.

References

ACARA. (2022a). ACARA Charter. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. https://www.acara.edu.au/docs/default-source/corporate-publications/20170301-acara-charter.pdf?sfvrsn=2

ACARA. (2022b). General Mathematics (Version 8.4). Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/senior-secondary-curriculum/mathematics/general-mathematics/?unit=Unit+1&unit=Unit+2&unit=Unit+3&unit=Unit+4

ACARA. (2023). Annual Report 2022-2023. https://www.acara.edu.au/docs/default-source/corporate-publications/acara-annual-report-2022-23.pdf

ACNC. (2024) Ecstra Foundation Limited. Annual Reporting, Financial Report 2024. https://www.acnc.gov.au/charity/charities/d28fc461-30ba-e811-a963-000d3ad244fd/documents/

ACNC. (2019) Ecstra Foundation Limited. Annual Reporting, Financial Report 2019. https://www.acnc.gov.au/charity/charities/d28fc461-30ba-e811-a963-000d3ad244fd/documents/

ASIC. (2003). Financial literacy in schools. https://download.asic.gov.au/media/1924489/what-do-you-want-to-do-with-fin-lit-schools-dp.pdf

Australian Constitution (1901). Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900.

Australian Curriculum (2024). Consumer and financial literacy: Year 9. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/curriculum-connections/dimensions/?id=46504&searchTerm=financial+literacy#dimension-content

Australian Government & ASIC. (2024). Money Smart for Teachers. MoneySmart.gov.au. https://moneysmart.gov.au/teaching/lesson-plans

Blue, L. & Brimble, M. (2014). Reframing the expectations of financial literacy education: Bringing back the reality. The FINSIA Journal of Applied Finance (JASSA), 2014(1), pp. 37-41. https:// eprints.qut.edu.au/115878/

Breckenridge, J. (2020). Understanding Economic and Financial Abuse in Intimate Partner Relationships. UNSW Sydney. https://rlc.org.au/sites/default/files/attachments/UNSW%20report%201%20-%20Financial%20Abuse%20and%20IPV%20-%20PDF%20version%20-%20Final.pdf

Chen, H. & Volpe, R.P. (2002). Gender differences in personal financial literacy among college students. Financial Services Review, 11(3), pp. 289-307. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A149166047/ AONE?u=anon~24b3b4a5&sid=googleScholar&xid=1a4d9cef

Collett, J. (2023). “Costing us a fortune”: Australians still failing basic financial literacy tests. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/money/planning-and-budgeting/costing-us-a-fortune-australians-still-failing-basic-financial-literacy-tests-20230810-p5dviu.html

Council of Australian Governments (2017) Project Agreement for MoneySmart Teaching. Federal Financial Relations. https://federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/sites/federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/files/2021-01/moneysmart_np.pdf

De Zwaan, L., & West, T. (2023). Financial Literacy of Young Australians. Financial Basics Foundation. https://financialbasics.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/FBF-Financial-Literacy-of-Young-Australians-March-2022.pdf

Department of Education. (2024). 2024–25 professional development subsidies now open. Australian Government. https://shorturl.at/qJjfB

Fernando, J. (2024). Financial literacy: What it is, and why it is so important. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/financial-literacy.asp

Garcia, E., & Weiss, E. (2017). Education inequalities at the school starting gate: Gaps, trends, and strategies to address them. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/education-inequalities-at-the-school-starting-gate/

Hendry, N., Hanckel, B., & Zhong, A. (2021). Navigating Uncertainty: Australian young adult investors and digital finance cultures. RMIT University and Western Sydney University. https://shorturl.at/Epzaw

International Network on Financial Education. (2023). Denmark Global Money Week. Global Money Week. https://www.globalmoneyweek.org/countries/155-denmark.html

McGhee, A. (2022). Australians double spending through buy now, pay later services, to $11.9bn. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-06-29/australians-double-spending-through-buy-now-pay-later-services/101191090

Murray, A. (2020). HILDA Survey. Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research; The University of Melbourne. https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda

Nazeri, H. (2024). Financial and Monetary Systems. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/01/longevity-economy-thriving-societies/

NSW Education Standards Authority. (2020). Commerce 7–10 NEW | NSW Education Standards. NSW Government. https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/learning-areas/hsie/commerce-7-10-2019

NZ Labour. (2023). Release: Compulsory Financial Skills in Schools. New Zealand Labour Party https://www.labour.org.nz/financial_skills_schools

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2024). Resilience of Australian Households and Businesses | Financial Stability Review – March 2024. Reserve Bank of Australia. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/fsr/2024/mar/resilience-of-australian-households-and-businesses.html

Rishworth, A. (2024). Increased funding for financially vulnerable people and communities. Ministers for the Department of Social Services. https://ministers.dss.gov.au/media-releases/14676

Singhal, P. (2017). Australian 15-year-olds declining in financial literacy: PISA Report, The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 May 2017. Accessed on 15 August 2018 at https://www.smh.com.au/education/australian-15yearolds-declining-in-financial-literacy-pisa-report-20170524- gwbqem.html

The Educator Australia. (2024). New report highlights Australia’s financial literacy gaps. https://shorturl.at/y5ySP

West, T. and Drew, N. (2023), "Abuse of enduring power of attorneys and real estate transactions in Australian courts", Journal of Financial Crime, Vol. 30 No. 5, pp. 1220-1230. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-08-2022-0175

Wood, D. (2023). Allianz survey: women have significantly lower financial literacy than men. KM Business Information Australia. https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/au/news/breaking-news/allianz-survey-women-have-significantly-lower-financial-literacy-than-men-456518.aspx

World Economic Forum. (2024). Denmark mandates financial literacy education from age 13. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/videos/denmark-teens-financial-literacy/#:~:text=Denmark%20has%20mandatory%20financial%20education

World Economic Forum. (2024). Denmark mandates financial literacy education from age 13. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/videos/denmark-teens-financial-literacy/#:~:text=Denmark%20has%20mandatory%20financial%20education

-------

The views and opinions expressed by Global Voices Fellows do not necessarily reflect those of the organisation or its staff.

.png)